Alpha Condé, Guinea's 82-year-old head of state, will this Sunday ask his country's 5.4 million voters for a third term, opening what promises to be a tense, high-stakes electoral season for West Africa, with contests soon following in Ivory Coast, Ghana and Niger.

If he fails to clinch outright victory with more than 50% of the vote, the president will probably have to face off against his leading opponent, Cellou Dalein Diallo, in a run-off that on past form that will probably spark violent confrontation on the streets of Conakry, the crowded capital city, crammed into a narrow peninsula jutting out into the Atlantic.

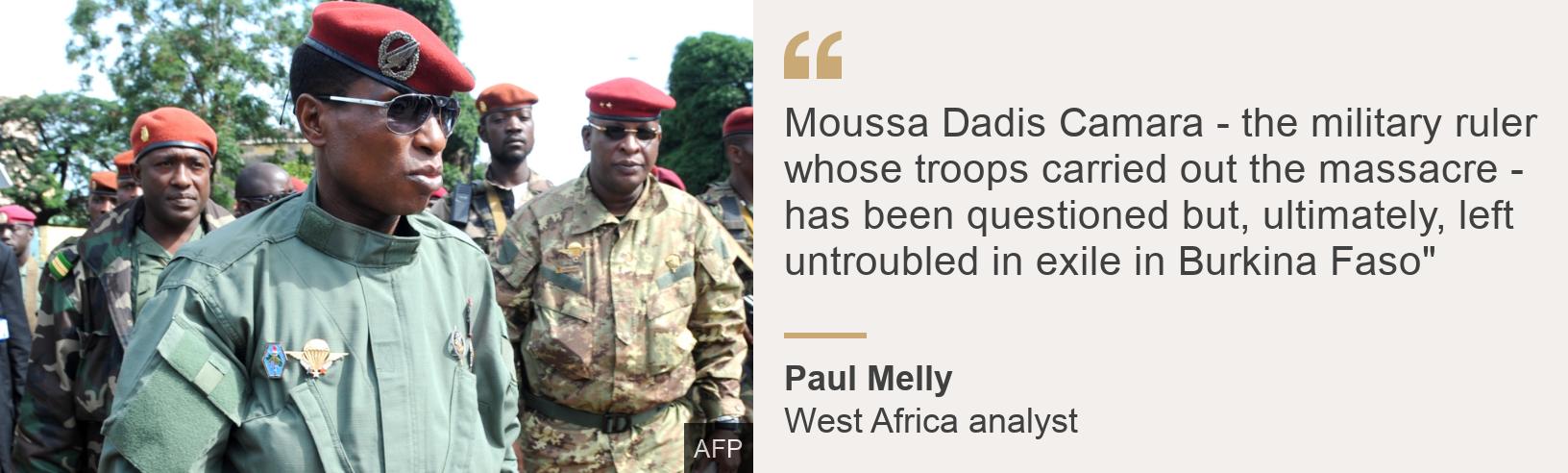

Mr Condé's accession to power in December 2010 was the first genuinely democratic handover in his country's 52-year independent history - a saga of authoritarian and military rule pockmarked with episodes of severe repression and spectacular brutality, the most recent of which had been the 28 September 2009 massacre, when troops killed at least 160 opposition supporters, and raped 110 women, attending a rally at the national stadium.

He had himself served jail time for challenging General Lansana Conté, who had ruled from 1984 to his death in 2008, and he faced a huge task to gradually reform the security forces and construct a democratically accountable state with a basic respect for human rights and transparent public finances.

Achievements

The past 10 years have brought significant progress.

Early fears of a comeback coup by army hardliners gradually faded, and the military has been at least partly reformed, with many officers sent into retirement.

A team of capable technocratic ministers has got the economy back on track, rebuilding a solid cooperative partnership with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the donor community.

Guinea has huge mineral wealth and regulation of the extractives sector has been overhauled.

Confidence among investors has recovered, opening up the prospect that Simandou, one of the world's largest untapped iron-ore deposits, might finally be exploited - creating thousands of new livelihoods and with construction of a new rail line to link the landlocked southern interior to the coast.

As one of the three countries severely affected by West Africa's 2014-16 Ebola outbreak - alongside neighbouring Sierra Leone and Liberia - Guinea developed experience in tackling infectious disease that it has been able to bring to bear in its response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

One of the grand old men of sub-Saharan politics, Mr Condé re-established Guinea's profile on the African diplomatic stage.

Disappointments

But serious problems persist, particularly in human rights.

Opposition figures such as Mr Diallo have suffered sporadic harassment, while political life is still scarred by periodic outbreaks of street violence between frustrated youthful demonstrators and security forces that, despite retraining, still frequently resort to lethal force to curb unrest.

Moreover, the long promised trial of the military figures indicted for the 28 September massacre has still not taken place, despite a sustained campaign by the families of victims, foreign diplomatic pressure and hints that the International Criminal Court (ICC) will step in if the Guinean authorities fail to act.

At least one of the soldiers formally indicted has actually held government office under Mr Condé, while Moussa Dadis Camara - the military ruler whose troops carried out the massacre - has been questioned but, ultimately, left untroubled in exile in Burkina Faso.

Capt Camara remains hugely popular in his home region, Guinée Forestière, and senior politicians seem reluctant to sanction any move that could threaten hopes of attracting support there.

In the 2015 election Mr Diallo even formed a bizarre electoral alliance with his camp, while a key ally of Capt Camara is a senior minister in Mr Condé's government.

Third-term controversy

That is the unsettled background contest for this year's election, which has been rendered hugely contentious by Mr Condé's determination to seek a third term - a move that has meant changing the constitution, through a referendum in March.

Guinea and Ebola:

The new constitution does not scrap two term limits, but resets the counter, so previous terms served do not count.

Early this year, the regional body Ecowas (the Economic Community of West African States) identified 2.5 million names of apparently fictional electors on the voters' register.

The opposition decided to boycott the referendum, giving Mr Condé an easy mandate.

In recent days, he has argued that this was a constitutional overhaul that he had long wished to carry out but felt that he could not prioritise during the early years of his administration.

But pressed over whether he has ambitions to be head of state for life, he has been evasive.

Although Mr Condé did not formally confirm that he would stand again, even early last year his ambition to do so was already common talk in Conakry - and a source of worry among other West African leaders, and European diplomats, fearing a renewed bout of instability in a country with such a long history of confrontational urban political violence.

There were hopes that the president could be persuaded to opt for a graceful elder statesman retirement. But his determination has been evident for many months